VE day and the hope for peace

Marigold Bentley reflects on the beginning of the end of World War II and the work for peace that continues.

My mother described to me how she and her mother cried all day when Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced that Britain was again at war on 3 September 1939. World War I had been so terrible only 21 years earlier. The memory of that war and its impact for my grandmother, and more so my grandfather, was a continual trauma. They found it unbearable to think of having to endure yet more war. But, despite the many hardships, during those six years of 1939 to 1945 there emerged a determination to not repeat the mistakes of the past.

So the end of war in 1945 was a joy and delight. My mum, who had grown up during the war, threw herself into International Voluntary Service for Peace and Family Relief Units, getting involved in work camps and community efforts to build a new Europe. She was alongside many Quakers who were involved in delivering relief across Europe in the 1940s and 1950s.

Theirs was the challenge of feeding, clothing and housing displaced people. For the Quakers involved, a fundamentally important part of what they did was to establish new relationships among the many displaced people. The aim was reconciliation and restoration of dignity.

This approach did not always go down well with the military who were required to treat the German people as the enemy, even after the war had ended. The principle of working to enable people to see one another as human and to be compassionate and tender has always been in direct contrast to the brutality of war. For Quakers, the understanding is that to prevent war, relationships have to be developed and common aims which benefit the many have to be the bedrock of new beginnings.

Confronting inhumanity

It is important to acknowledge the limited knowledge that ordinary people had about what was really going on in Germany in the 1930s and during the war. Whilst many Quakers and others were conscientious objectors and undertook various forms of alternative non-military service, some felt that fascism could only be defeated by joining the war effort. The situation clearly posed enormous religious challenges and difficult choices which individual Friends had to take.

It was a huge shock to the Quaker relief workers who entered Bergen-Belsen six days after the British military to see first-hand what had been done in the concentration camps. Even now, 75 years on it is hard to comprehend the cruelty inflicted when all the evidence and personal accounts are available for us to see. Cruelty of such extremes must always to be challenged but nonviolently in order for humanity to break out of the bloody cycle of war.

The relief at the end of World War II in Europe, following decades of war and the threat of war, was enormous. It was tempered though, by the continuation of war in the Far East, which did not end until August 1945 after the dropping of nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Building a world without war

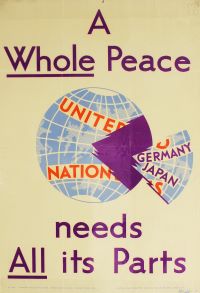

The end of World War II brought with it a renewed determination to build a world without war. The United Nations was founded with the support of every major world power on 24 October 1945, "determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war".

Quakers have worked at the UN since that time, with offices in Geneva and New York. A large number of visionary organisations were created to pool resources and direct them to relief of suffering, including Christian Aid.

75 years on we remind ourselves of the lessons of the first half of the twentieth century. The need to disarm, the need to provide for need not greed and the collective requirement to organise so that people and planet flourish. Wherever we are, we continue to listen to the whisperings of hope, and act on the endless opportunities for peace.