How can educators respond to events in Palestine and Israel?

It feels more important than ever to teach peace, but it can seem like it's never been harder. How can we be brave educators? Ellis Brooks shares his thoughts on some of the issues schools are facing.

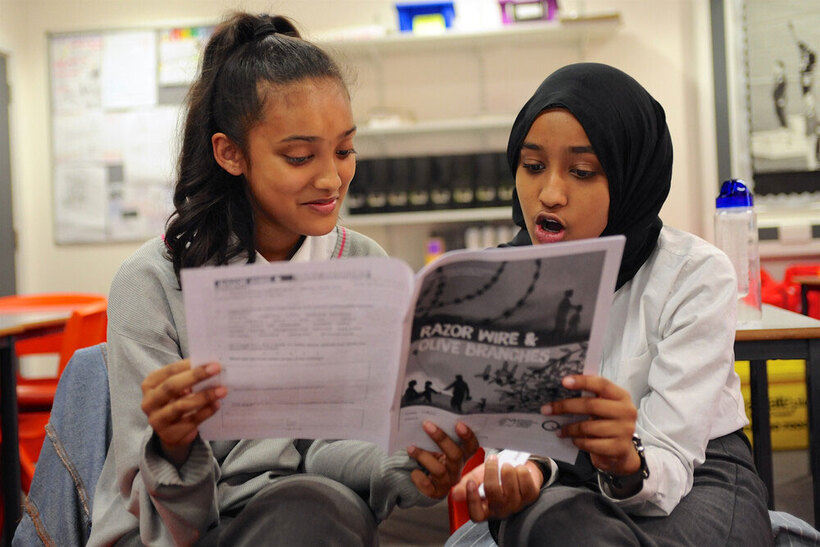

Quakers are making Razor Wire & Olive Branches resources downloadable for free and the physical pack available at a discount. We've sign-posted more resources for educators below.

What's happening in schools?

Recent years saw a fall-off in teaching of 'the Arab Israeli conflict' in England. In 2018, Education Scotland was pressured to unpublish resources on Palestine and Israel for schools. Perhaps the subject is depressing. Perhaps teachers fear it is too controversial, or just plain difficult.

Yet teaching materials on Palestine and Israel have seen rapid uptake since violence spilt into the headlines, pointing to a thirst for understanding. This surge will be partly to answer children's urgent questions, and partly a response to the acute needs of children – Jewish, Muslim, Arab – any who feel a connection with what's happening. Some children – and teachers – will be treated as if the news is 'about them' because of their identity, whether they want it to be or not. Others will feel their pain is ignored.

Sadly, there is hate and bullying in schools. When conflict escalates in Israel and Palestine, antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents increase. Teachers, parents, carers will be concerned about intolerance in their communities and how they navigate these challenges and prevent harm.

Not in spite of these challenges but because of them, it is important for schools to facilitate brave and compassionate spaces to learn about both conflict and peacebuilding in Palestine and Israel.

What is the government telling schools?

The Education Secretary Gillian Keegan has written to schools in England reminding them to challenge behaviour that celebrates violence or stigmatises others. She also highlighted schools' duty to impartiality. Keegan condemned the Hamas attacks and expressed government's solidarity with Israel. Essential messages, although incomplete.

The Secretary of State isn't a teacher, so is perhaps exempt from their professional obligations, but her message is literally partial because of what was left out: news of Palestinians facing violence. Islamophobia is alluded to as a seeming afterthought and there's no mention of international law, even though it's part of the statutory citizenship curriculum and the rule of law is promoted as a fundamental British value.

There is a danger that this will confuse and confound teaching.

What is impartiality?

The 1996 Education Act for England says schools must provide "balanced presentation of opposing views", and there's substantial guidance about what that means. The challenge for teachers is to go beyond a crude weighing-scales approach to build ethical, informed citizenship. This can mean the teacher taking different stances ranging from impartial facilitator to advocate for one side, giving learners a range of perspectives and the tools to evaluate them.

Critical educators recognise their own impartiality can never be perfect. Teachers – like all of us – are not necessarily conscious of their own biases. What feels impartial to one silences the pain of another.

As Edward Said wrote, "Every empire… tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, that its mission is not to plunder and control but to educate and liberate."

In educating on Palestine and Israel, it's useful to draw on the framework of principled impartiality. This approach informs the human rights monitoring of the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI). It means being 'for' neither side, but pro human rights and international law. Ecumenical Accompaniers' reports adhere to this approach, providing eyewitness accounts that can be useful for the UN Human Rights Council and for the classroom.

Humanise with heart and head

[QUOTE-START]

“Perhaps my words will assist in awakening the world, which is currently sleeping while millions cry."

- Hamza N. Ibrahim, Palestinian teacher, We Are Not Numbers

[QUOTE-END]

Principled impartiality asks a lot: active listening, critical thinking, empathy, ethical reasoning, understanding of history, religion, geography, knowledge of human rights, and deep curiosity about a context people devote lifetimes to studying. Yet it's often adults who are timid, while children can be fearless and farsighted learners.

Despite the mesmerising scale of violence, learning can start with a story, humanising the people behind statistics. It might be a warrior-turned-peacemaker, someone enduring loss, standing up for justice or reaching out across divides. They might be religious, a farmer, a refugee, a parent, a child; they will be a person we can try to see and understand. Stories can provoke questions and learning inquiry.

Education in Palestine and Israel

[QUOTE-START]

“Direct contact with the Palestinian partners taught me a fascinating lesson in what it means to be human, getting to know the other and diminishing the despair."

- Niv Sarig, brother to Guy, who was killed by a sniper while in the Israeli Army in 1996 (via Parents Circle Families forum).

[QUOTE-END]

Before we bemoan our challenges, it's worth noting the difficulties faced by teachers in Palestine and Israel. Whatever the curriculum says, children bear the brunt of sirens and rockets, schools demolished, children detained or killed.

When schools open, it doesn't mean they're free from conflict. Hamas runs education in Gaza, while the Palestinian Authority (PA) governs schools in the West Bank, although the UN agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) also operates a lot of schools. UNRWA has been castigated by Hamas simply for teaching about the Holocaust. The Palestinian Authority's textbooks are fiercely criticised by some in Israel, although the current volumes were found not to be antisemitic by an independent review.

In Israel, textbooks have been accused of dehumanising Arabs and politicising history. The Parents Circle – Families Forum (PCFF), a joint Israeli-Palestinian organisation of families who have lost immediate relatives to the conflict, was banned from Israeli schools by the Ministry of Education.

Despite this shrinking teaching space, I have faith there are those teaching humanity in whatever space they can find.

"My heart fills with agony," wrote Shahd Safi, a Gazan teacher in a 2022 poem. "But I will not lose hope."

Humanity calls to us to teach ourselves and each other.