Targets vs delivery: addressing Scotland’s greenhouse gas emissions

Andrew Tomlinson shares some of the challenges of meeting Scotland's climate targets.

Recently Scotland published its greenhouse gas emissions statistics for 2020. These data showed a fall in emissions, and yet many, including myself, hold serious concerns that Scotland will not meet its ambitious climate targets.

Last month, as part of a delegation from Stop Climate Chaos Scotland (a coalition of over 60 civil society organisations in Scotland campaigning against Climate Change), I met with Chris Stark, Chief Executive of the Climate Change Committee (CCC). The CCC is an independent public body, formed under the Climate Change Act, to advise the UK, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governments, parliaments and assemblies on tackling and preparing for climate change.

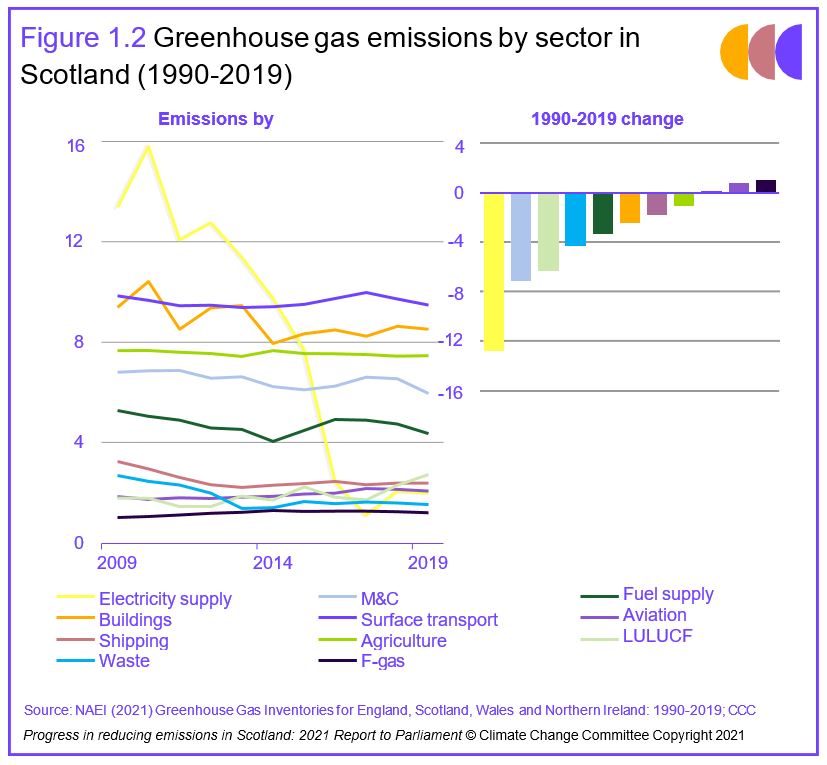

Chris started the meeting by showing us the graph below:

The graph comes from the most recent CCC progress report for Scotland and shows emissions reductions by sector in Scotland over time. The only meaningful decline in emissions is in electricity supply, with all other sectors largely flat lining. Some sectors such as surface transport, aviation and fracked gas show an increase since 1990.

Ambitious targets

But, I hear you say, Scotland is supposed to be good on climate. It has some of the most ambitious emissions reduction targets in the world. And it is one of the only industrialised nations to have committed finance to address the loss and damage that the climate crisis is inflicting on the global south.

But it is also true that good targets will not meet themselves. While the emissions figures for 2020 are welcome they are largely an exception in a landscape in which Scotland has consistently missed its climate targets.

By the Scottish Government's own admission, the fall in emissions was largely the result of the public health interventions introduced to restrict the spread of Covid-19. As the pandemic restrictions have eased, emissions have started to rebound. Data on car usage, for example, shows traffic in certain areas is now higher than pre-pandemic levels.

There is a real and growing risk that Scotland will not meet its ambition to be carbon neutral by 2045, while its target of a 75% reduction in emissions by 2030 seems increasingly unlikely. The targets are good but we are currently not seeing the type and level of activity that will be required to achieve them.

Targets vs delivery

So what steps do we need to see?

The CCC is currently undertaking work to give us a more accurate picture about the steps needed. If we just take the example of domestic heat it gives us a good idea of the shortfall. For Scotland to decarbonise its domestic heating we need to see around 64,000 heat pumps installed per year by 2025, peaking at around 200,000 a year in the late 2020s. Currently we are only managing between 3000 and 4000 a year.

The number of domestic gas boilers coming to the end of their life each year in Scotland is only around 100,000 a year. Even if we were simply replacing these gas boilers with heat pumps, which we aren't doing, this would not be enough. We would also need to replace another 100,000.

Not only are we not replacing gas boilers in sufficient quantities, but there are currently new houses being built in Scotland which rely on fossil fuels for heat. It's also unclear whether there are enough qualified tradespersons who can install these new low carbon systems. If we are to meet our targets we should be seeing the number of people trained in these professions significantly ramping up already, with bespoke college courses and an increase in apprenticeships.

Many of these challenges are acknowledged by the government and, speaking with civil servants, they assure us that they are both aware of the issue and are exploring significant interventions that will allow them to close these gaps. However, no information about these steps is public yet and the clock is ticking.

Political action and risks

Returning to our meeting with Chris Stark from the Climate Change Committee, he explained that for politicians, delivery of climate ambitions carries significantly more political risk than target setting. If we look again at housing, retrofitting houses is potentially messy work that can be disruptive to people's lives, and if a trader gets something wrong then it could be the government's reputation that takes the hit.

Scottish Government civil servants have begun work on the next Climate Change Plan. Due to be published at the end of 2024, this plan is expected to chart the path to achieving Scotland's climate targets. As we continue to meet with ministers and civil servants about this we are emphasising this gap between targets and delivery.

For the government, bridging this gap will not be straightforward and will come with considerable political risk. Our role then is to emphasise, not only the greater risks to not acting, but also the public support for taking these difficult steps.

If you have time over the next few weeks, then do write to your MSPs to emphasise your support for the government taking the serious, if difficult, measures to address the climate crisis. 2020 doesn't have to be an exception, it can be the start of a consistent pattern of Scotland meeting its greenhouse gas emissions targets.