Not zero: why we should be wary of ‘net zero’ climate targets

Olivia Hanks explains why carbon emission targets need to move on from 'net zero'.

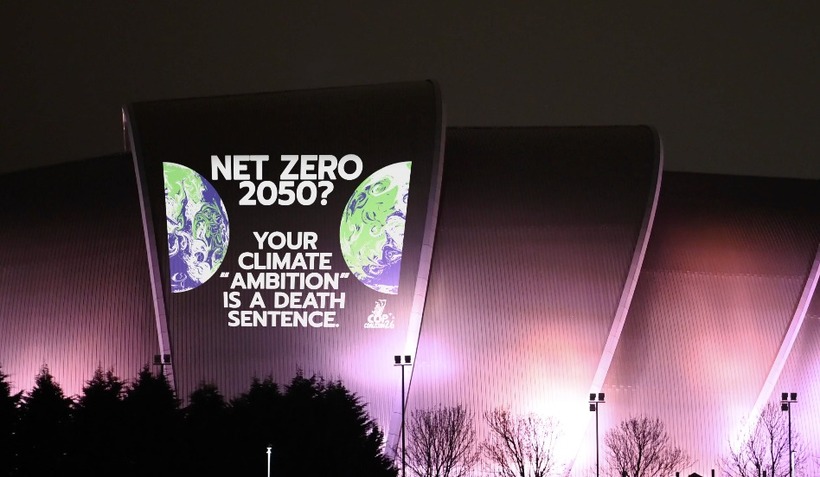

As the UK was hosting its 'Climate Ambition Summit' last December, the COP26 Coalition projected a message on to the Scottish Event Campus in Glasgow, where the UN climate talks will be held. The message read "Net Zero 2050? Your Climate 'Ambition' Is A Death Sentence".

You're probably familiar with the argument, made repeatedly by scientists, campaigners, and countries most vulnerable to climate breakdown, that a 2050 target is much too late. We are set to overshoot 1.5 degrees of warming within the next few years; and every year of delay makes the impacts worse and the task harder. But what of 'net zero'?

Cover for business as usual

In June 2019, the then Prime Minister Theresa May announced that the UK was committing to reduce its emissions to 'net zero' by 2050, after sustained pressure from campaigners to introduce a new target aligned with the Paris Agreement. Quakers in Britain cautiously welcomed the news, calling it “a significant step in the right direction" but warning that pledges must quickly be matched with policies.

Two years on, it is now abundantly clear that 'net zero' is being used by many governments and corporations as cover for business as usual.

The term 'net zero' arises from the likelihood that whatever action we take, there will be some residual emissions which we need to deal with by removing carbon from the atmosphere. The safest and most reliable way to do this is by protecting forests and other natural 'carbon sinks'. However, their capacity is extremely limited – we still need to reduce our emissions to almost zero.

Instead, the UK government and big polluters are pinning their hopes on negative emissions technologies (NETs) – technological approaches to removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. NETs are increasingly being factored into emissions reduction plans, despite being completely unproven at scale.

Companies with 'net zero' targets include Shell, BP and Rolls-Royce. This shows that big polluters now know they have to be seen to be serious about climate – but they're not making any noticeable shift away from their high-carbon core activities.

Land grabs

The most commonly cited NET is bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). This involves massively increasing the burning of trees and crops for bioenergy, capturing the carbon emitted and burying it underground.

Even if this were to work – which is highly uncertain – the large-scale deployment of BECCS would risk pushing us beyond other planetary boundaries including freshwater use and soil health. Estimates of the amount of land required are as high as 3000 million hectares – twice the total amount of land currently under cultivation globally. You can find out more in this briefing from Friends of the Earth International (PDF).

Even simpler land-based approaches such as tree planting need to be approached with caution. Where do corporations and rich countries plan to plant all these trees? Will it be on lands used for food growing by some of the poorest people in the world? Will they be monoculture plantations replacing diverse habitat?

These promised 'nature-based solutions' risk replicating the imperialist models which got us into this crisis in the first place – with countries in the Global South now acting as a carbon sink for pollution from the most industrialised nations.

Speaking the truth

Quakers in Britain no longer use the term 'net zero' in our advocacy and campaigning work, except to refer to others' existing pledges which use this language. Sadly, in its current use by the UK government, it no longer appears to be a step in the right direction. Rather, it has been shown to be a weasel word, the latest corporate greenwash given currency by many well-intentioned users (including us).

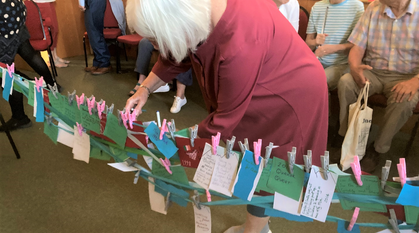

Quakers try to "speak the truth in plainness" (Quaker faith & practice 19.46). What does this mean for our own climate commitments? Since the Canterbury Commitment in 2011, Quaker meetings have been grappling with how to reduce their own carbon emissions and take action on the climate crisis.

The wave of 'climate emergency' declarations in 2019 has renewed the energy around this work. But for many organisations, including Quaker meetings, it remains unclear what exactly they can do.

If your meeting or group also chooses to reject the term 'net zero', there is plenty you can still commit to. Take a look at some of our suggestions (PDF).

A commitment for change

A commitment can be a catalyst for all kinds of positive changes, even if we do not know when we start exactly how we will reach our destination. However, given the scale of denial and deception around climate breakdown, we also need to be careful in our use of language.

There is much we can do, but Quaker meetings cannot eliminate their carbon emissions entirely without wider changes to our economy and society – that is why climate action means working for system change, not just individual change. To imply otherwise risks letting governments off the hook.